Abstract

This article examines the participation of the Peruvian Armed Forces in the promotion of sustainable development from a multidimensional perspective. Through a documentary analysis, it studies the institutional contributions in the economic, social, environmental and political dimensions, within the framework of national security and defense. It is argued that the Armed Forces, in addition to their traditional role in the defense of sovereignty, have the capacity to actively intervene in development processes through multisectoral actions that strengthen governance, national resilience and territorial cohesion. In this context, the normative, institutional and operational mechanisms that allow them to articulate their actions with the strategic objectives of the State are identified. The study concludes that, with adequate planning and inter-institutional coordination, the Armed Forces can play a key role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially in vulnerable and hard-to-reach areas.

Keywords: Armed Forces, sustainable development, security, national defense, multisectoral participation, governance.

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) defined sustainable development in 1987 through the report presented by Brundtland, entitled Our Common Future. It addressed environmental challenges, pointing out that economic growth and globalization could be counterproductive. Therefore, solutions were analyzed to face the difficulties of industrial growth and population increase (De las Casas et al. 2019). In Spain, the term “sustainable development” was translated as “desarrollo sostenible” (Noboa et al. 2021), while in Latin American countries such as Mexico it was translated as “desarrollo sustentable”. Although both words are understood in a similar way, the UN has promoted reports to clarify their use (Larrouyet 2015), which has led experts to debate on their application according to region, discipline and time. It is observed that “sustainable development” has greater preference in the economic and environmental spheres over time (Gómez and Garduño 2020).

In recent decades, sustainable development has been a topic of concern and interest in the academic, social and political fields, especially in the context of a climate crisis, biodiversity degradation and social disparities generated by increasing poverty, which fosters exclusion. These problems represent a latent threat (Garrido 2005), as they constitute an existential danger to human progress and ecosystem balance, which drives the need for integrated approaches and innovative solutions (Parra 2021).

Peru is a diverse country in its geography and cultural composition, where multiple complexities interweave the challenge of sustainable development (De la Cruz Gamonal 2003; Sullca et al. 2015). Although the Peruvian State enacted the General Environmental Law No. 28611 and the National Environmental Policy (PNA) to 2030, challenges persist. Illegal logging, informal mining and illicit drug trafficking (IDT) threaten the integrity of ecosystems and undermine efforts to achieve sustainable development (Ministerio del Ambiente 2005, 2021; El Peruano 2021), driving deforestation of vast forested areas. According to a 2018 Ministry of Environment report, the Peruvian Amazon has lost approximately 23 000 hectares of forest, with notable increases in Madre de Dios, Loreto, San Martin and Ucayali. In addition, illegal mining contributed between 15% and 22% of the gold exported by Peru in 2016, according to a documentary by China Central Television, constituting a serious danger to the environment and national development (Antonio 2020). Against this backdrop, sustainable development is seriously compromised, underscoring the need for the Peruvian State to mobilize all its resources, including its military power, to ensure compliance. In this regard, no studies have been conducted on the participation of the Armed Forces in sustainable development or on their understanding and importance.

Having delineated the problematic reality, the question arises: How does the participation of the Armed Forces allow for sustainable development in Peru? The study analyzed the participation of the Armed Forces in Peru’s sustainable development. The specific objectives are to examine their contribution to the economic, social and environmental development of the country.

Chuquimajo (2022) investigated the role of the Armed Forces in the social development of the Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley (VRAEM), a region with little state presence, and highlighted their fight against terrorism and drug trafficking, as well as their valuable contribution to human welfare in Canayre. Similarly, Miranda (2022) emphasized the military’s role in the adaptation and mitigation of environmental changes, especially through the reinforcement of the Jungle Battalions in the Amazon.

Córdova (2022) emphasized the timely response of the Armed Forces to natural disasters, highlighting the need for adequate resources and effective doctrine. Likewise, Alcalde (2022) points out that these institutions provide support in social conflicts, although he warns of limitations in their training and operational cohesion during prolonged missions.

Orbegozo (2022) reveals that, despite their multisectoral campaigns, the Armed Forces face significant limitations in planning and coordination, which weakens their impact on local development in the VRAEM. In this regard, Olivera (2022) criticizes the deficiencies in the response capacity of the 3rd Armored Brigade to natural disasters due to lack of training and adequate resources.

Gonzáles (2022) postulates that the absence of integration in the multisectoral security and defense policy restricts the effectiveness of the Army in Disaster Risk Management (DRM). Complementarily, Ríos (2022) evidences the shortage of personnel in the fight against drug trafficking in the VRAEM, which impedes the implementation of government policies.

Olaya (2021) analyzes the importance of the Amazon from a geopolitical perspective and the need for a strategic vision to confront threats such as illegal logging and drug trafficking. In this sense, Arrieta (2021) proposes a model to integrate science and technology in the Armed Forces, improving their contribution to sustainable development and national defense.

Ayala (2021) analyzes the impact of environmental deterioration on the perception of national security, and proposes greater participation of the Armed Forces in the protection of natural resources in Tambopata. Anto (2020); on the other hand, stresses the need for military presence in Madre de Dios to combat illegal gold mining and illegal logging, while Ramírez (2020) highlights the role of the Armed Forces in natural disaster mitigation and their ability to provide support in remote areas.

De las Casas et al. (2019) examine the work of the 35th Jungle Brigade in environmental protection and economic development in Caballo Cocha, concluding that its presence deters illicit activities and promotes both environmental integrity and economic growth. Internationally, Sierra et al. (2021) highlighted that the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) promotes sustainability and post-conflict development, in accordance with United Nations (UN) guidelines. However, they warn that the absence of the state in territories previously controlled by the FARC has facilitated the illegal exploitation of resources.

Castro and Gutiérrez (2020) developed a four-phase model to assess the needs of populations affected by guerrilla violence, whose exodus deteriorated their social development. Despite the fact that the peace agreement allowed the implementation of several projects, threats persist. In this line, Valencia (2020) points out the importance of comprehensive planning for sustainable development that includes social investment plans adapted to local conditions and with citizen participation.

Sandoval et al. (2019) examined the impact of the armed conflict in the Zones Most Affected by the Conflict (ZOMAC) in Colombia, and conclude that fiscal policy has prioritized revenue increase without improving public expenditure management. Consequently, they recommend policies aimed at reducing inequality in localities such as Aguachica, promoting the sustainable use of resources. On the other hand, in 2014, Ecuador updated its legislation to define the role of its Armed Forces in environmental protection, while Brazil adopted a sovereign approach that integrates natural resource conservation with its economic development strategy (Jimenez 2020). Knox (2018) emphasizes that international obligations regarding sustainable development and environmental protection must be reflected in national legislation, especially in contexts marked by socio-environmental conflicts.

Sustainable development seeks to harmonize economic growth, environmental conservation and social well-being. In 2015, the international community adopted the 2030 Agenda, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in multiple areas. Achieving them requires the collaboration of governments, the private sector and civil society, actors who contribute creativity, knowledge, technology and financial resources (Envera 2019). However, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted progress in this area, exacerbating poverty, inequality, and job loss (Ortega 2021).

This study approaches sustainable development as a general theory that involves the implementation of economic policies, respect for the environment and the promotion of social equity, encompassing three fundamental dimensions: economic, ecological and social. According to Baker (2015) and Jeronen (2020), these are essential to balance present and future needs.

Governments face the challenge of reconciling economic growth with social equity and environmental sustainability. Dourojeanni (2000) argues that sustainability implies meeting the needs of the present without compromising the possibilities of future generations. Gutiérrez (2007) examines sustainable development within the framework of development theories, highlighting the interaction between economic growth, social justice and ecological conservation. In contrast, Vargas (2008) questions the viability of sustainable development, warning that phenomena such as hunger and deforestation continue to threaten the future.

Llamas et al. (2010) point out that environmental awareness increased in the 1990s, which allowed the consolidation of a key definition of sustainable development as the satisfaction of present needs without jeopardizing future ones. The theory of economic development focuses on the creation of wealth and employment. Vargas (2008) states that to ensure sustainable economic cycles, effective regulations and efficient public management are required. This theory also stresses the need for a balance between state, society and economy to achieve effective development.

Pearce et al. (1994) emphasize that international collaboration is key to addressing environmental challenges and fostering an equitable global economy. Artaraz (2002) points out that the 1973 economic crisis questioned the model of growth based on unlimited resources, which opened the debate on the compatibility between the economic and the environmental.

The theory of environmental development values biodiversity conservation and promotes the care of ecosystems (Posso et al. 2022). Along the same lines, ecological economics – inspired by Georgescu-Roegen’s bioeconomy – conceives the economy as a subsystem of nature (CESGIR 2022). Catao and Carneiro (2022) specify that the State must regulate the exploitation of natural resources, seeking a balance between conservation and development. For its part, the theory of social development focuses on education and professional training as pillars of sustainable development (Carvajal 2021). Mae (2011), in line with Vygotsky, highlights the relevance of social interaction in cognitive development.

From a conceptual approach, sustainable development is understood as a balance between economic progress, social justice and environmental protection, as defined in the 1987 Brundtland Report (López et al. 2005). Tello (2006) describes economic development as the generation of wealth and employment through the efficient use of resources. On the other hand, Gómez (2014) and Orellana (2020) stress the need for responsible environmental management as a basis for sustainability.

Finally, social development seeks to ensure equity and the general well-being of the population (Montes 2018), enhancing inclusion and quality of life as fundamental components of sustainable development (Madrueño 2017). In this sense, the UN Agenda 2030 highlights the interdependence between the economic, social and environmental dimensions as axes of a truly sustainable development (Alonso 2024).

Methodology

The present research adopted a qualitative approach, suitable for analyzing in depth specific phenomena of reality through various strategies, methods and instruments. This privileges the quality as the main unit of analysis, which facilitates the identification of categories and the construction of systemic relationships between the parts and the observed phenomenon, in accordance with the hermeneutic-interpretative paradigm (Vargas 2011).

Regarding the categories of analysis, Hernández (2014) argues that these, together with their respective subcategories, allow grouping relevant information and represent fundamental concepts of the study. Their adequate organization facilitates the interpretation of the data and contributes to the theoretical construction. Along the same lines, Rabinovich and Kacen (2010) point out that the identification of relationships between categories, typical of the qualitative approach, constitutes a key input for the theoretical formulation.

Based on the objectives of the study, three central categories linked to the concept of sustainable development -economic, social and environmental- were defined, each with their respective subcategories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Categories and subcategories of analysis

| Categories Subcategories |

| Sustainable development Economic development Economic growth

Labor employment Social development Security General welfare Environmental development Environmental protection Protection of natural resources |

Source: Artaraz 2002, cited in Alonso 2024.

Artaraz (2002) argues that sustainable development admits diverse interpretations; however, they all coincide in the need for it to be economically viable, environmentally responsible and socially equitable. These dimensions constitute the central categories of this study.

Three techniques were used for data collection: in-depth interviews, documentary research and direct observation. According to Vargas (2011), the application of at least two techniques guarantees triangulation and strengthens the validity of the results obtained.

Results

The results obtained confirm that the Peruvian Armed Forces play a relevant role in promoting sustainable development, in agreement with national and international literature (Chuquimajo 2022; Miranda 2022; Sierra et al. 2021). In the economic dimension, the protection of strategic infrastructure and the safeguarding of border areas have favored investment and regional integration; however, the lack of resources and planning limits the scope of these contributions. In the social dimension, civic actions and humanitarian assistance have contributed to improving well-being in vulnerable areas, although multisectoral coordination still presents challenges. In the environmental dimension, participation in the protection of natural areas and the fight against environmental crime is significant, but training and logistical resources are insufficient.

In the social sphere, they carry out operations aimed at neutralizing terrorism and drug trafficking. They also intervene in violent social conflicts, in support of the Peruvian National Police (PNP), in those areas that have been declared in a state of emergency, in accordance with Article 137 of the Peruvian Constitution. In such circumstances, they assume control of internal order in accordance with the supreme decree issued by the President of the Republic. At the same time, they promote general welfare through civic actions, social and community programs, such as the Itinerant Social Action Platforms (PIAS), and the construction of bridges and roads by the Engineering Battalions of the Peruvian Army (EP).

In the environmental area, the Armed Forces intervene in the protection of the environment in accordance with legislative decrees 1137, 1138 and 1139, which regulate the functions of the Armed Forces. They also protect natural resources through interdiction operations against illegal activities such as indiscriminate mining and logging (Alonso 2024).

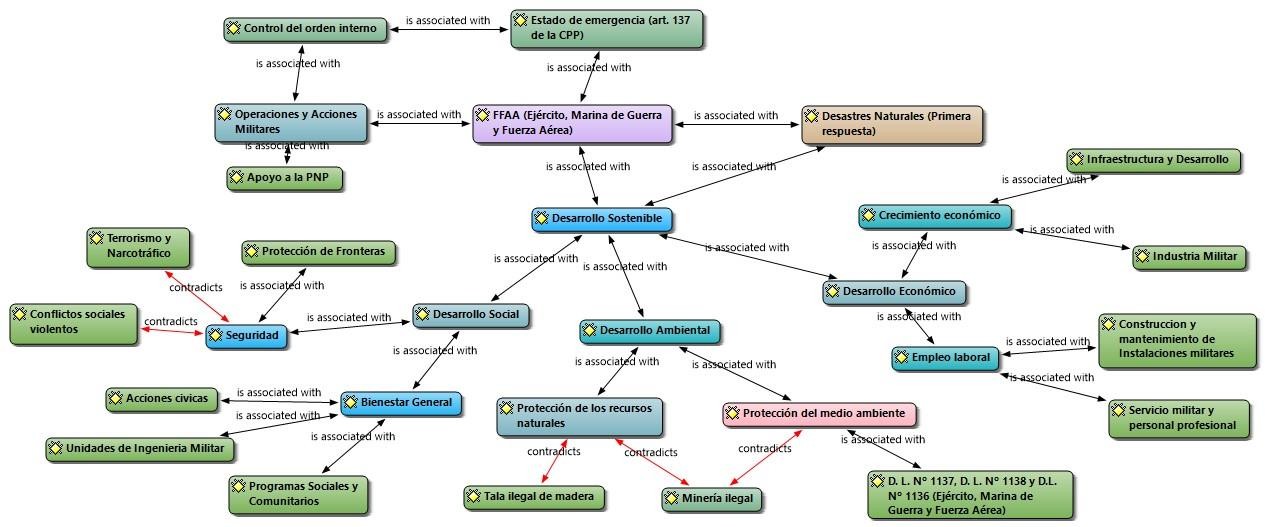

In order to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the contributions of the Armed Forces to the sustainable development of the country, Figure 1 presents a graphic representation of their main areas of intervention. This semantic network, elaborated with ATLAS.ti software, allows visualizing the connections between their functions in the economic, social and environmental dimensions, as well as their impact on national dynamics, within the framework of current regulations and institutional actions implemented in recent years (Alonso 2024).

Participation of the Armed Forces in economic, social and environmental development.

Note: Semantic network elaborated in ATLAS.ti software.

Source: Alonso 2024.

Discussion

From the analysis of the results and through the triangulation of instruments, a precise interpretation of the role of the Armed Forces in Peru’s sustainable development was obtained. Article 165 of the Political Constitution of Peru establishes that these institutions – made up of the Peruvian Army (EP), the Peruvian Navy (MGP) and the Peruvian Air Force (FAP) – constitute a strategic resource for the State, as they face various challenges linked to the promotion of development (Miranda 2022). Chávez (2020) indicates that, due to their infrastructure and resources, the Armed Forces operate in areas of difficult access, where state presence is limited.

The concept of sustainable development is based on the balanced integration of the economic, social and environmental spheres (Artaraz 2002; Alonso et al. 2024), which is essential for the progress of societies, as Envera (2019) argues. Llamas et al. (2010) state that this principle seeks to satisfy current needs without compromising those of future generations. Along these lines, Dourojeanni (2000) considers it essential to adopt policies aimed at the responsible use of natural resources and the preservation of the environment.

According to Article 171 of the Political Constitution of Peru, the Armed Forces not only perform national defense functions, but also actively participate in disaster management, with timely responses to crises that contribute to economic and social reactivation (Córdova 2022; Ramírez 2020; Sullca et al. 2015). In this logic, the Ministry of Defense (MINDEF) promotes the development of the military industry, generating employment and strengthening the national economy (Libro Blanco de la Defensa Nacional 2005).

Several factors, such as illegal mining and social conflicts, represent relevant threats to sustainable development (Antonio 2020; Alcalde 2022). The Armed Forces, under the leadership of the Joint Command, execute operations in support of the Peruvian National Police in areas declared in emergency, according to the framework established by Legislative Decree 1095 (De las Casas et al. 2019; Chiabra 2019).

The Voluntary Military Service (SMV) provides technical and professional training, which contributes to employment and economic growth (Alor and Espinoza 2023; Sanchez 2022). Professional military personnel constitute a fundamental part of the labor force, indirectly influencing economic development by guaranteeing the security and stability of the country (Libro Blanco de la Defensa Nacional 2005).

In the social sphere, the Armed Forces protect against threats such as terrorism and drug trafficking, especially in areas such as the VRAEM (Ríos 2022). Military operations in these areas are crucial to reduce the influence of criminal groups and maintain national security. In addition, they carry out multisectoral civic actions in remote communities, providing medical services and social support (Chuquimajo 2022).

Military Engineering Units and Itinerant Social Support Platforms (PIAS) contribute significantly to the construction of infrastructure and the provision of services in remote regions (Ramirez 2020; Donayre 2021; Avellaneda-Vasquez 2024). These actions demonstrate the commitment of the Armed Forces to the integral development of the country.

Regarding environmental development, the Armed Forces protect the environment and natural resources, in accordance with the provisions of Legislative Decree 1142 (El Peruano 2012). The General Directorate of Captaincy and Coast Guard (DICAPI) controls activities in maritime and fluvial spaces (Rugel 2020). In turn, units deployed in the Amazon play a relevant role in environmental conservation (Arce 2023).

Illegal activities, such as mining and logging, represent significant threats. The Armed Forces carry out operations to neutralize these practices and protect natural resources (Anto 2020; Ayala 2021). Their presence in border zones is also vital for the security and socioeconomic development of these areas (De las Casas et al. 2019; Piñeros et al. 2020).

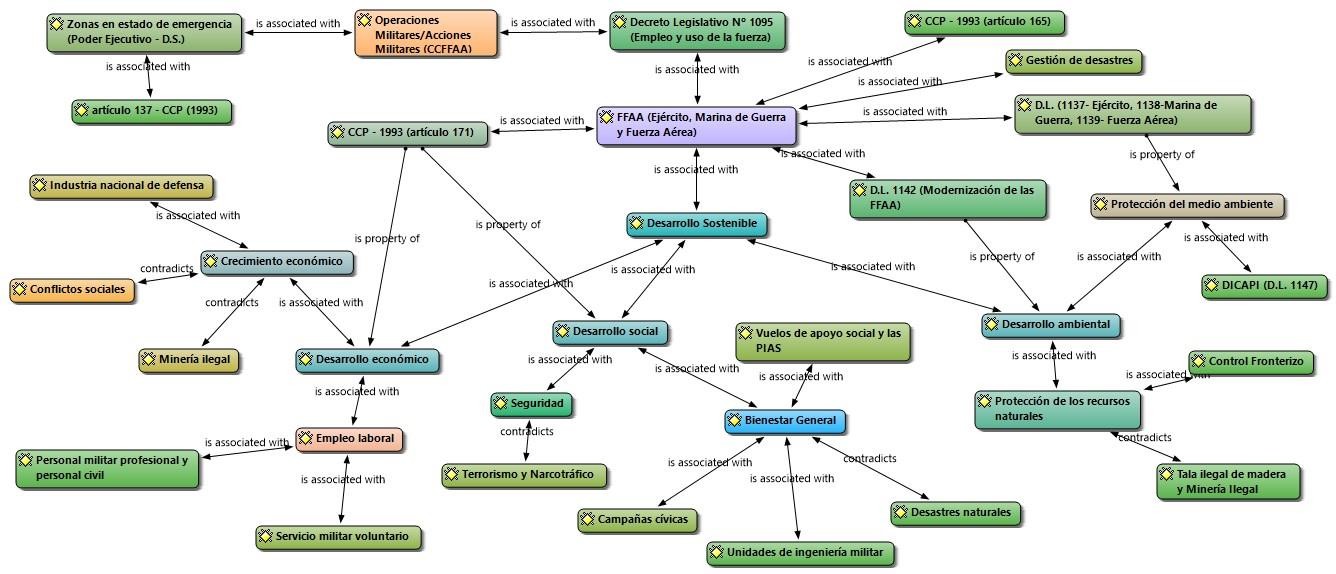

Figure 2 below graphically synthesizes the triangulation of research instruments and the participation of the Armed Forces in Peru’s sustainable development.

Figure 2. Semantic network of research instrument triangulation

Note: Semantic network elaborated in ATLAS.ti software.

Source: Alonso 2024.

Conclusions

The Armed Forces play a fundamental role in Peru’s sustainable development, integrating the economic, social and environmental spheres. Their intervention in risk management and infrastructure support in remote areas makes an outstanding contribution to national stability and progress, standing out for their ability to operate in areas where the presence of other state entities is limited.

Beyond their defensive role, the Armed Forces drive economic development by generating employment in the military industry and combating illegal mining, as well as addressing social conflicts that hinder economic growth. These actions are essential to create a secure and stable environment, which is indispensable for sustainable economic development.

In the social sphere, the Armed Forces play an essential role in improving general welfare, through multisectoral civic operations, the provision of medical services, the construction of infrastructure and the carrying out of aeromedical evacuations in remote communities. These interventions make up for the limited state presence in such areas and significantly improve the quality of life of their inhabitants, in addition to strengthening citizen security.

Although environmental protection is not explicitly mentioned in Article 171 of the Political Constitution of Peru, the Armed Forces play a relevant role in environmental conservation and the protection of natural resources, as established in Legislative Decree No. 1142, Law of Bases for the Modernization of the Armed Forces. This legal framework recognizes the importance of their contribution to the preservation of the natural environment as an integral part of national sustainable development.

Endnotes

- María Isabel Aguado, Carmen María Echevarría and Luis Javier Barrutia, “El desarrollo sostenible a lo largo de la historia del pensamiento económico,” Revista de Economía, Mindial 21 (2009): 87-110, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/866/86611886004.pdf.

- María Elena Alcalde, Análisis de la capacidad de sostenimiento de las Fuerzas Armadas para intervenir en conflictos sociales: Caso conflicto de Tía María, período 2018-2019, Master’s thesis, Centro de Altos Estudios Nacionales – EPG, 2022, https://acortar.link/TlwQzV.

- Teófilo Ricardo Alonso, Participation of the Armed Forces in the sustainable development of Peru, PhD thesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo – EPG, 2024, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/152502.

- Teófilo Ciro Alonso and Iván Egocheaga, Análisis de la profesionalización de las especialidades de Material de Guerra e Intendencia en el Ejército del Perú, master’s thesis, Escuela Superior de Guerra del Ejército – EPG, 2019, http://repositorio.esge.edu.pe/handle/ESGEEPG/196.

- Teófilo Ricardo Alonso, José Cano, Brayan Quispe and Katherine Santa Cruz, “Sustainable development and its implications in the Peruvian Amazon. A systematic review,” Revista Científica Aula Virtual 5, no. 12 (2024): 289-304, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11301897.

- Elio Alor and Zoila Espinoza, El Servicio Militar y su Impacto en el Cumplimiento de la Misión constitucional Asignadas a las Fuerzas Armadas del Perú 1999-2013, 2023, https://acortar.link/hu4h0r.

- Rosa María Anto, “Impacto de la minería y tala ilegal en el desarrollo y la Seguridad Nacional,” Revista de Ciencia e Investigación en Defensa – CAEN 1, no. 2 (2020): 50- 60, https://doi.org/10.58211/recide.v1i2.23.

- Raúl de Antonio, “Impact of Illegal Mining and Logging on Development and National Security,” 1, no. 2 (February 17, 2020), https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1024-4124.

- Raúl Ricardo Arce, “Amazonía, Biodiversidad, Ríos Voladores y Seguridad Nacional,” Revista de Ciencia e Investigación en Defensa – CAEN 4, no. 2 (2023): 57-73, https://doi.org/10.58211/recide.v4i2.114.

- Victor Manuel Arias and Maria Camila Giraldo, “Scientific rigor in qualitative research,” Investigación y Educación en Enfermería 29, no. 3 (2011): 500-514, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1052/105222406020.pdf.

- Pedro Fernando Arrieta, Science, technology and innovation in the Armed Forces: Strategies from an integrated model for national development and defense, 2018- 2019, PhD thesis, Centro de Altos Estudios Nacionales – EPG, 2021, https://acortar.link/OzTfkk.

- María Artaraz, “Theory of the three dimensions of sustainable development,” Ecosystems (2002), https://acortar.link/ic4okj.

- Juan Avellaneda-Vásquez, “Derechos lingüísticos de los pueblos indígenas u originarios en el Perú. Un análisis a partir de las Plataformas Itinerantes de Acción Social (PIAS),” APIENTIA & IUSTITIA (2024): 53-75, https://doi.org/10.35626/sapientia.9.5.117.

- Guillermo César Ayala, La Visión Holística de la participación de las Fuerzas Armadas en la Defensa de los Recursos Naturales en la Reserva Nacional Tambopata, PhD thesis, Centro de Altos Estudios Nacionales – EPG, 2021.

- Susan Baker, Sustainable development, London: Routledge, 2015, https://acortar.link/6QnmKf.

- Alfredo Betalleluz, “The Role of the Armed Forces in the Containment and Management of Social Conflicts in Peru,” 20 March 2024, https://acortar.link/QVLD5d.

- Daniel Borish, Ashlee Cunsolo, Ian Mauro, Cheryl Dewey, and Sherilee L. Harper, “Moving images, moving methods: Advancing documentary film for qualitative research,” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20 (2021): 16094069211013646, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211013646.

- Diana Cadenas, “El rigor en la investigación cualitativa: técnicas de análisis, credibilidad, transferibilidad y confirmabilidad,” Sinopsis Educativa. Revista venezolana de investigación 7, no. 1 (2016): 17-26, https://acortar.link/sXBiBA.

- María Rosa Carvajal, “Professional training for the unemployed and sustainable development: factors limiting economic and social development,” Prisma Social 34 (2021): 267-297, https://acortar.link/TxBfyI.

- María Angélica Castro and Diana Patricia Gutiérrez, “Modelo de Intervención Integral como aporte a la construcción y fortalecimiento del tejido social en Bogotá, articulado con los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible, para diferentes actores del conflicto armado en Colombia,” IBEROAMERICANA, Bogotá (2020), https://acortar.link/g5gX9a.

- Carlos Catao and Rodrigo Carneiro, “The promotion of the socio-environmental state and environmental justice in the mining activities chamber of minas gerais,” Revista de Gestào Social e Ambiental 16, no. 2 (2022): 1-18, https://doi.org/10.24857/rgsa.v16n2-008.

- Rafael Cervantes and José Villaseñor, “Complexity and economic development in Latin America, 1950-2018,” Revista Latinoamericana de Economía 53, no. 209 (2022): 27-52, https://doi.org/10.22201/iiec.20078951e.2022.209.69795.

- CESGIR, “Así se sacudió la teoría económica,” Portfolio (2022), https://acortar.link/roSxS4.

- Ngan D. Chau and Ravi Kanbur, “Past, Present and Future of Economic Development,” in Towards a New Enlightenment? A Transcendent Decade, BBVA, 2018, https://acortar.link/dX01tC.

- Luis Chavez, “Participation of the Armed Forces in National Development,” Journal of Defense Science and Research 1, no. 2 (2020): 64-76, https://acortar.link/MKN7Dk.

- Roberto Chiabra, “The Armed Forces. New Scenarios, New Missions and Greater Responsibilities,” April 29, 2019, https://acortar.link/A3LT0V.

- Jonhy Chuquimajo Huamantumba, “Participation of the Armed Forces in humanitarian aid actions and human development in the localities of the VRAEM:2019,” Revista de Ciencia e Investigación en Defensa – CAEN 3, no. 1 (2022): 21-31, https://doi.org/10.58211/recide.v3i1.5.

- Comenta YT, Youtube, April 27, 2023, https://acortar.link/PfpAFY.

- Political Constitution of Peru, December 29, 1993, https://acortar.link/teOWNA.

- Antonio Wilfredo Córdova, Participation of the Armed Forces in Disaster Risk Management and the rehabilitation process in the Piura region. Período 2019-2020, Master’s thesis, Centro de Altos Estudios Nacionales – EPG, 2022, https://acortar.link/p02d2Y.

- Arthur Cropley, Introduction to qualitative research methods. A research handbook for patient and public involvement researchers, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526136527.00012.

- Legislative Decree 1134, “Approves the Law of Organization and Functions of the Ministry of Defense,” December 9, 2012, https://acortar.link/U3DPnc.

- Alfredo De la Cruz Gamonal, “Desarrollo humano sostenible y medio ambiente en el Perú,” 2003, https://acortar.link/xX8Ysn.

- Bartolomé de las Casas, Raúl Sánchez and Mario Castillo, Capacidades de la 35a Brigada de Selva para la protección del medio ambiente y su relación con el desarrollo sostenible en su ámbito de responsabilidad, Master’s thesis, Escuela Superior de Guerra del Ejército del Perú – EPG, 2019, https://acortar.link/SclRBt.

- Daniel Jesús Donayre, Propuesta de capacidad de la ingeniería militar que contribuya a mejorar la infraestructura educativa del Centro de Educación Técnica Productiva N°005 Tumbes, master’s thesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo, 2021, https://acortar.link/ASzTvT.

- Axel Dourojeanni, “Management Procedures for Sustainable Development,” August 2000, https://acortar.link/cYG1Mm.

- Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, “Building theories from case study research,” Academy of Management Review 14, no. 4 (1989): 532-550, https://doi.org/10.2307/258557.

- El Comercio, “Cambio climático: por qué los desastres son más humanos que naturales?”, September 12, 2021, https://acortar.link/HXqacF.

- El Peruano, “Ley de Bases para la Modernización de las Fuerzas Armadas – Decreto Legislativo Nº 1142,” 2012, https://acortar.link/xQs6Nn.

- El Peruano, “Lucha contra las drogas no se detiene y será constante,” September 11, 2021, https://acortar.link/649Qe5.

- Envera, “Sustainable Development Goals,” August 8, 2019, https://acortar.link/2QwEDh.

- Juan Manuel Erazo, “Rigor científico en las prácticas de investigación cualitativa,” Ciencia, docencia y tecnología XXII, no. 42 (2011): 107-136, https://acortar.link/aHLecc.

- Fuerza Popular, “Ley que regula la participación de las Fuerzas Armadas en el desarrollo sostenible del país,” Congreso de la República, Lima, 2019, https://acortar.link/66Qyax.

- Francisco Javier Garrido, “Desarrollo sostenible y Agenda 21”, 2005, https://acortar.link/V6P5qR.

- Francisco Godiño, “Universidad, sociedad del conocimiento y desarrollo económico: trilogía para la prosperidad social,” Revista de Filosofía, Centro de Estudios Filosóficos, Universidad del Zulia 39, no. 101 (2022): 480-493, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6788966.

- Carlos Julio Gómez, “From Sustainable Development to Environmental Sustainability,” Revista Facultad de Ciencias Económicas 22, no. 1 (2014), https://acortar.link/hjkPWo.

- Rodrigo Gómez and Ricardo Garduño, “Desarrollo sustentable o desarrollo sostenible, una aclaración al debate,” Tecnura 24, no. 64 (2020): 117-133, https://doi.org/10.14483/22487638.15102.

- Ángela María González, “Aspectos éticos de la investigación cualitativa,” Revista Ibero Americana de Educación 29 (2002): 85-103, https://acortar.link/CgPQ58.

- Francisco Guillén and Diana Elida, “Qualitative Research: Phenomenological Method,” Purposes and Representations 7, no. 1 (2019): 201-229, https://acortar.link/kWkeiE.

- John G. Gurley and Edward S. Shaw, “Financial aspects of economic development,” The American Economic Review 45, no. 4 (1995): 515-538, https://acortar.link/791uvo.

- Gustavo Enrique Gutiérrez, “De las teorías del desarrollo al desarrollo sustentable. History of the Construction of a Multidisciplinary Approach,” Trayectorias IX, no. 25 (September-December 2007): 45-60, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/607/60715120006.pdf.

- Tessa L. Haven and Gert L. Van, “Preregistering qualitative research,” Accountability in Research 26, no. 3 (2019): 229-244, https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1580147.

- Roberto Hernández Sampieri, Carlos Fernández Collado, and Pilar Baptista Lucio, Metodología de la Investigación, 6th edition, Mexico: McGRAW-HILL / INTERAMERICANA EDITORES, S.A. DE C.V., 2014.

- Pedro S. Izcara, Manual de Investigación Cualitativa, Mexico: Fontamara, 2014.

- Eila Jeronen, “Sustainable development,” Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management (2020): 1-7, https://acortar.link/FjfHjP.

- Victor Raul Jimenez, “Armed Forces and Public Security: Comparative Study of Ecuadorian and Brazilian Laws,” Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad 15, no. 2 (2020): 57-72, https://doi.org/10.18359/ries.4620.

- Hanna Kallio, Anneli M. Pietilä, Martin Johnson, and Mari Kangasniemi, “Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide,” Journal of Advanced Nursing 72, no. 12 (2016): 2954-2965, https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031.

- John Knox, “Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment,” 2018, https://acortar.link/YaH6SS.

- Carolina Larrouyet, Desarrollo sustentable: origen, evolución y su implementación para el cuidado del planeta, trabajo final integrador, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Argentina, 2015, https://acortar.link/Duqiej.

- Ministry of Defense, Libro Blanco de la Defensa Nacional, 2005.

- Sara R. Llamas, Francisco Á. Muñoz, Trinidad G. Maraver and Gregorio B. Senés, “El papel de las ciudades en el desarrollo sostenible: el caso del programa ciudad 21 en Andalucía (España),” EURE, Revista Latinoamericana De Estudios Urbano Regionales 36, no. 109 (2010): 63-88, https://acortar.link/S72FrU.

- Rafael C. López, Ernesto López-Hernández, and Patricia I. Ancona, “Sustainable or sustainable development: a conceptual definition,” Horizonte Sanitario 4, no. 2 (2005), https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4578/457845044002.pdf.

- Juan Luna-Nemecio, Sergio Tobón and Luis G. Juárez-Hernández, “Chemical extraction of trace elements from dredged sediments into a circular economy perspective: Case study on Malmfjärden Bay, south-eastern Sweden,” Resources, Environment and Sustainability 2, no. 100007 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resenv.2020.100007.

- Antonio Rafael Madrueño, “Assessment of Socio-Economic Development through Country Classifications: A Cluster Analysis of the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and the European Union (EU),” Revista de Economía Mundial 47 (2017): 43-64, http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86654076002.

- Silvia Susana Mae, “The Theory of Social Development,” 2011, https://acortar.link/IfprZC.

- Juan Mancilla, Ricardo Placido, Arturo Torres, Jorge Bravo and Juan Orozco, Turismo y desarrollo económico, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, 2021, https://acortar.link/PyBJjH.

- María Magdalena Martínez, Epistemología y Metodología Cualitativa en las Ciencias Sociales, México: Trillas, 2008, https://acortar.link/rZ8f78.

- James O. Midgley, Social development: The developmental perspective in social welfare, 1995, https://acortar.link/Bn250b.

- Jennifer Milne and Kathy Oberle, “Enhancing rigor in qualitative description,” Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing 32, no. 6 (2005): 413-420, https://acortar.link/1w6Isy.

- Ministry of Environment, “Política Nacional del Ambiente al 2030,” July 25, 2021, https://acortar.link/ce4a0H.

- Ministry of Defense, “Plataforma digital única del Estado Peruano,” May 20, 2024, https://acortar.link/v7fM7B.

- Ministry of Environment, “Ley General del Ambiente – Ley Nº 28611”, October 15, 2005, https://acortar.link/JZz5nq.

- Ministry of the Environment, “Unidad Funcional de Delitos Ambientales – UNIDA”, March 8, 2021, https://acortar.link/XGmGwZ.

- Carlos C. Montes, Miradas regionales sobre desarrollo económico y social, Lima, Peru: Universidad del Pacífico, 2018.

- Silvia V. Murguía and Héctor Z. Ronzón, “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): reviewing Goal 8 in Mexico at the halfway point,” Equidad y Desarrollo 42 (2023): 108- 133, https://doi.org/10.19052/eq.vol1.iss42.6.

- Sofía J. Noboa, Ana Vergara-Romero, Rocío Sorhegui-Ortega, and Luis Garnica- Jarrin, “Rethinking sustainable development in the territory,” RES NON VERBA 11, no. 1 (2021): 19-33, https://doi.org/10.21855/resnonverba.v11i1.500.

- Carmen Y. Obegozo, Feasibility of Multisectoral Civic Campaigns of the Joint Command of the Armed Forces. Estudio de caso en la comunidad nativa de Teoría, distrito de Llaylla, provincia de Satipo, Junín, Master’s thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2022, https://acortar.link/BDUyve.

- María Mercedes Olaya, “Geopolitical vision of the Peruvian Amazon and its social, economic and political impact,” Revista de Ciencia e Investigación en Defensa- CAEN 2, no. 1 (2021): 44-53, https://doi.org/10.58211/recide.v2i1.52.

- Tania Olivera, Análisis de las Capacidades de la 3º Brigada Armada para enfrentar a Desastres Naturales en la Región Moquegua, 2020, master’s thesis, Escuela Superior de Guerra – EPG, 2022, https://acortar.link/MMwslU.

- Natalia P. Orellana, “Environmental Sustainability”, Economipedia, 2020, https://acortar.link/kjcliX.

- José Luis Ortega, Hosteltur, September 23, 2021, https://acortar.link/h5IU05.

- Blanca Parra, “Towards a sustainability paradigm for V. R. Potter’s bioethics: between sustainable development, ecodevelopment and environmental rationality,” Cuadernos de Filosofía Latinoamericana 42, no. 124 (2021), https://doi.org/10.15332/25005375.6604.

- David W. Pearce, “Sustainable development,” Environment and Planning A 24, no. 9 (1992): 1273-1283, https://doi.org/10.1068/a241273.

- Pedro Planas, “El desarrollo sostenible: una aproximación conceptual,” Revista de Economía y Estadística 38, no. 2 (2000): 7-36, https://acortar.link/3w2XqQ.

- United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2020, New York: UNDP, 2020, https://acortar.link/0h4k0k.

- United Nations Environment Programme, Global Environment Outlook GEO-6: Summary for Policymakers, Nairobi: UN Environment, 2019, https://acortar.link/7e4k6v.

- Rafael Quispe, “National Security and Sustainable Development in Peru,” Journal of Defense Science and Research – CAEN 2, no. 1 (2021): 25-34, https://acortar.link/6a0k6v.

- Rosa María Ramírez, “El desarrollo sostenible y la educación ambiental,” Educación y Futuro 21 (2009): 15-32, https://acortar.link/2d0k6v.

- Redacción Gestión, “El Perú y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible,” Gestión, September 25, 2021, https://acortar.link/5b0k6v.

- Redacción ONU, “La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible,” UN News, 2021, https://acortar.link/3c0k6v.

- Peru 21 Editorial Staff, “What are the Sustainable Development Goals?”, Peru 21, September 27, 2021, https://acortar.link/1a0k6v.

- RPP Newsroom, “What is sustainable development and why is it important for Peru?”, RPP Noticias, September 22, 2021, https://acortar.link/9d0k6v.

- Rosa María Rodríguez, “Sustainable development: concepts and applications,” International Journal of Sustainability, Technology and Humanism 2 (2007): 23-45, https://acortar.link/8e0k6v.

- Rosa María Rodríguez and Ana María González, “Education for sustainable development: a literature review,” Educación XXI 13, no. 2 (2010): 109-128, https://acortar.link/7f0k6v.

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Estrategia Nacional de Educación Ambiental para la Sustentabilidad en México, Mexico: SEMARNAT, 2017, https://acortar.link/6g0k6v.

- Sergio Serrano, “El desarrollo sostenible: una visión desde la economía ecológica,” Revista de Economía Crítica 18 (2014): 45-62, https://acortar.link/5h0k6v.

- Susana Cortina, “Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Development,” Isegoría 37 (2007): 7-22, https://acortar.link/4i0k6v.

- Tatiana Roa, “El desarrollo sostenible: una visión crítica,” Revista de Estudios Sociales15 (2003): 45-58, https://acortar.link/3j0k6v.

- UNESCO, Education for the Sustainable Development Goals: learning objectives, Paris: UNESCO, 2017, https://acortar.link/2k0k6v.

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Manual de buenas prácticas para el desarrollo sostenible, Mexico: UNAM, 2019, https://acortar.link/1l0k6v.

- World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987, https://acortar.link/0m0k6v.

- Yolanda Salinas, “El desarrollo sostenible: una mirada desde la educación,” Educación y Futuro 22 (2010): 33-50, https://acortar.link/9n0k6v.

- Yolanda Salinas and María José Martínez, “Environmental education and sustainable development: a literature review,” Educación y Futuro 23 (2011): 51-68, https://acortar.link/8o0k6v.